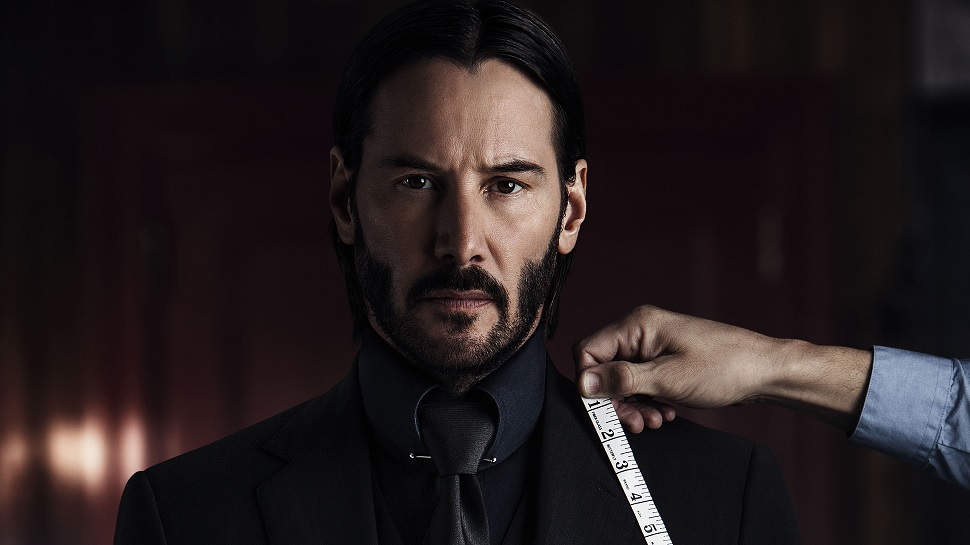

“Are you working?” This (or some paraphrasing of it) is a frequent refrain in John Wick: Chapter 2. It’s a fluid, almost shape-shifting phrase among the assassins which populate Chad Stahleski’s sophomore feature. Sometimes a greeting, sometimes an expression of pity, sometimes an implicit accusation. It channels all of these ideas and emotions through a very simple concept: work, a word which seems euphemistic to the viewer in this context. It is, after all, referring to the abhorrent act of killing human beings in exchange for money. But to wave this off as a joke is to miss this film’s seriousness about the craft and expertise involved in its action. The titular hero and on-again, off-again hitman (Keanu Reeves) doesn’t meet his clients in dark alleys or accept payment in duffel bags kicked under a table. Instead, he punches in at one of the many hotels used by the cabal of international assassins of which he is a part, trading ostentatious gold coins for his services. All the while opaque procedural issues are smoothed over by a watchful and unusually well-groomed Ian McShane over dinner, the group resembling a cross between the Illuminati and a teamster’s union.

If this sounds absurd, that means the film is having its desired effect. The first John Wick is often mocked (endearingly so, but still mocked) for the disproportionate, even farcical, scale of Wick’s quest for revenge. For the loss of his car and his dog, Wick goes on a bloody rampage against dozens of gangsters whose only beef with him was getting in his way. The contrast between the triteness of this plot and the scale and brutality of the action seems intentional and even humorous; we are supposed to revel in the absurdity of a man who would respond to a vicious but ultimately petty attack with mass murder. In the background was the mysterious and unnamed assassins’ order, a metaphor for the underworld which Wick was to re-enter and an almost Lynchian texture to sate the cinephiles who were drawn to the film. Weirdness for the sake of weirdness.

The second film is, if anything, even stranger. After what he had hoped would be a brief return from retirement, Wick is forced to honor a blood pact with Italian crime lord Santino D’Antonio (Riccardo Scamarcio) by assassinating D’Antonio’s sister (Claudia Gerini). He completes the mission, only to be betrayed by his client and hunted by his fellow assassins, forcing him to (surprise) kill countless people to get to D’Antonio. These scenarios are no more absurd than any of the action that drives them. Wick reels off two, three, even four consecutive headshots to start a shootout. When the ammo runs low, Wick turns to his superhuman dexterity and… “creative” faculties in the use of sharp objects. John Wick gained its cult following in no small part thanks to this penchant for plentiful, memorable killings. Online webpages track Wick’s total kills (as high as 84 for the first, 128 for the second), the methods of killing (varied), and even the accuracy of his marksmanship (high).

Chapter 2 steers right into this appeal from the opening scenes, wherein Wick reclaims his stolen car only to use it as a swerving, swinging blunt object with which to batter hapless mobsters. The film periodically cuts to the head baddie in his office, wide-eyed and grimacing at the violence he can’t see but can surely imagine. These close-ups might reflect the audience goggling the screen, incredulous yet captivated by the carnage, wondering whether the film is willing (able?) to crank the action up another notch. The answer is yes. Every time. The film is full of these moments, anticipation followed by surprise and extremity. In this fashion, much of the film plays more like a gory version of a Jackie Chan action comedy than most other contemporary action thrillers. One scene features Wick and rival hitman Cassian (Common) stalking each other in and around a New York subway station trying to kill the other without attracting the attention of surrounding bystanders. They walk casually, trying to pick the other off with pistols tucked into their chests as the clueless New Yorkers go on about their business. The civilians seem still unmoved by a silent yet quite visible knife fight on one of the train cars, even at its grisly conclusion. Only after the doors open does everyone rush out, a punchline almost five minutes in the making. The sequence feels like a Buster Keaton film; clever sight gags undergirded by technical precision and athletic prowess.

For as well as Chapter 2 functions as a comedy, like Keaton or Chan films, its DNA is all action. Stahleski spent most of his Hollywood career in stunt work (including turns as Reeves’ stunt double in The Matrix films) and his attention to and pride in the craft is obvious. All the action is impeccably choreographed and rehearsed to perfection, but Stahleski’s work also shows an affection absent from many of his contemporaries. The camera is pulled back, frequently still, and he will allow long sequences of movement to transpire within a single shot. But within all this action there are some gestures at a deeper psychology; Wick says aloud that the dog in the first film represents his failed attempt to move on from the death of his wife. In this sense, John Wick was arguably never about revenge, it was about falling back into old habits to fill a gap in your life. If the first film is about dealing with grief by burying yourself in work, then Chapter 2 is a celebration of dedicating your life to the pursuit of excellence in a craft. Though his words tell us that Wick is reluctant to dive back into the underworld of thugs and assassins, his body says differently. His every move is vigorous and purposeful; his face is lean and focused. He’s not happy, per se, but he is alive in a way that is absent in his earlier moping. The film basks in him, gleefully following each motion of said body as it systematically destroys the bodies of others. As much as this film is about Wick, its central concern is the mastery of a craft: stunt work in the film, assassination in the story. Chapter 2 does not portray the act of killing as immoral or futile like Park Chan Wook’s Oldboy, nor does it try to force an arbitrary moral justification for it like Pierre Morel’s Taken. It is simply amoral. It is simply “work”.

This is why Chapter 2’s deeper dive into the assassins’ underworld ultimately redounds to the film’s benefit. Far from the pathologized rage that defines most violent action films, Chapter 2 is guided by the contours of ceremony and bureaucracy. The organization’s guidelines are motivated primarily by utility instead of abstract values; the conflict between rival assassins makes them seem less mortal foes and more like competitive coworkers. There is enmity to be sure, but it is tempered by a grudging respect for the institutions in which they operate. One of the film’s funniest moments comes when, after a bloody and protracted fistfight, Wick and Cassian are made to respect the neutral ground of one of the assassins’ many hotels. They share drinks after a stern talking to from McShane, glowering at each other and presumably planning the other’s grisly end. The characters spend the bulk of the film probing the rules of their mutual workplace, testing how far they can go in their conflict while staying inside acceptable limits. The climactic moment of violence is tellingly not even the most extreme killing. Far from it, it is actually mundane by the gory and aestheticized standards Stahleski has set. The moment is followed by stillness and silence instead of the careening forward momentum of most of the film’s action. The shock is not because a human life has been taken, but because one of the cardinal rules of this world has been violated. For the inhabitants of this film, the latter is far more appalling than the former.