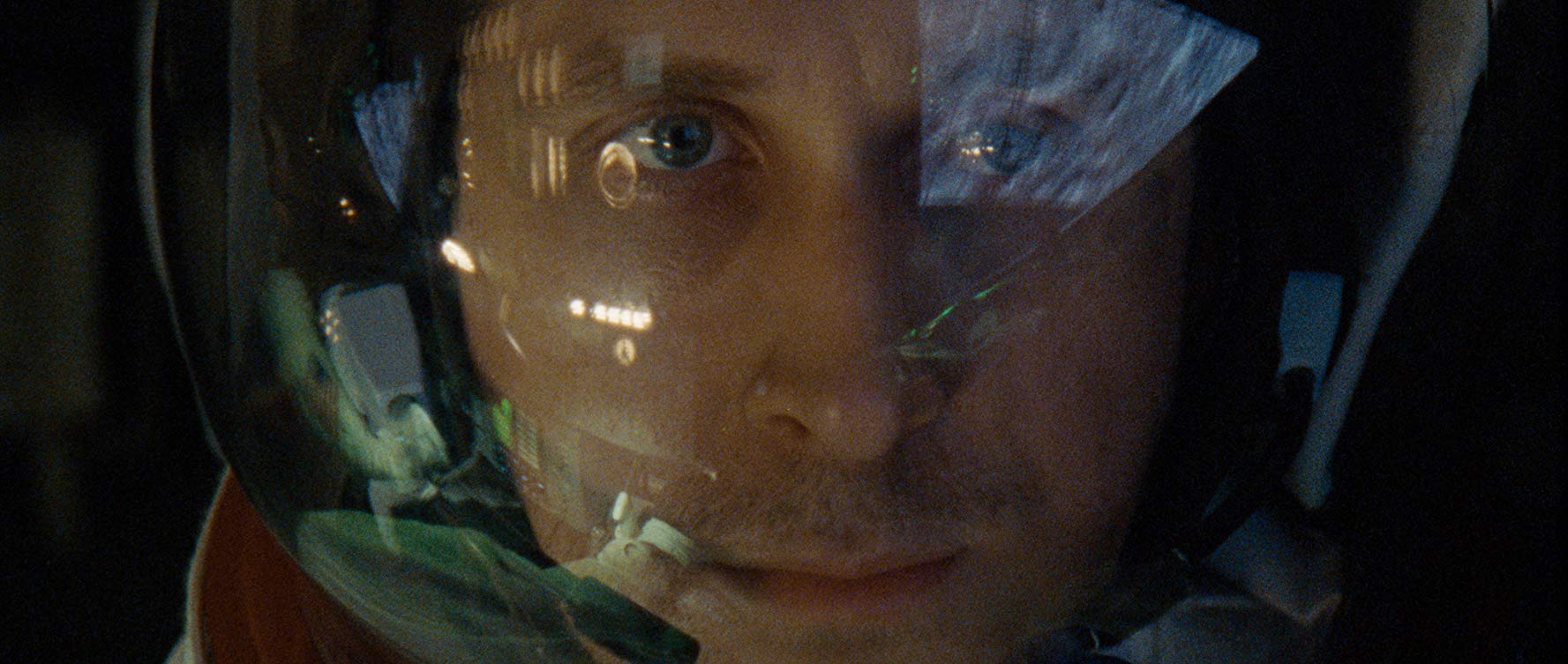

There is a single window on screen. It is compact, ovate like an airplane’s, and hardly reveals any detail of the space outside, but it is Neil Armstrong’s eye into the abyss. It is also auteur director Damien Chazelle’s scope into the story of the first moon landing in human history—airtight, subtle, and yet executing a holistic immersiveness from the shadows.

Every piece of the film, based on the biography by James R. Hansen, seems to fit perfectly with every one of the others, creating a near- perfect balance between style and substance, which shows, above all else, the level of control that exists between the scenes. First Man has one motivating element: perspective. Chazelle and cinematographer Linus Sandgren seem less interested in showing spectacle (although there’s no shortage of it in First Man) than they are in placing the viewer in Armstrong’s position—which is not only in the cockpit, but also in America during the 1960s, which saw the development of the contemporary civil rights movement, as well as a new industrialized enemy in the Soviet Union—and its own space program.

Chazelle knows his actors are exceptional and that the story—enlivened by Josh Singer’s meticulously researched script about Neil Armstrong, not the moon landing—is deeply personal, so he makes sure to capture their expressions and subtle sensibilities in gritty, unforgiving close-ups. Shorter, wider lenses placed closer to subjects are used in personal scenes, with establishing shots being replaced by introductory close-ups, or distant shots from the astronaut’s viewpoint in place of what would normally be a static third person’s. Chazelle goes hand-held throughout the entire movie, save for a couple grounded/mounted shots where it works in very different but still incredibly textured cinematic overtones. Pretty much every frame in First Man is perfect—in color, in framing, in light balance, and in composition.

In First Man, as in all of Chazelle’s films, the sound design is glorious—perfectly crafted to match the audible experience of air and space travel. Rarely has sound stood out so vibrantly in a film where the main spectacle seems to be the visual one, and it really goes to show how Chazelle, who has previously espoused his proficiency in this arena in films such as La La Land (2016), Whiplash (2014), and his first project, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2007), spared no creative expense injecting Singer’s compelling and authentic script with a sound, recorded and mixed by Ai-Ling Lee and Milly Iatrou, that ranges from the helpless shoveling of cemetery dirt to the boisterous roar of the engines attached to Apollo 11.

First Man’s score is composed by frequent Chazelle collaborator Justin Hurwitz, and only adds to that intensity, providing support where it is needed, but ducking out when the perspective needs to be sharpened. The soundtrack, which provides the much-needed historical consciousness beneath the physics and engineering, includes this incredible use of Gil Scott-Heron’s “Whitey on the Moon.” Chazelle clearly has a deep appreciation for the soundtrack of any film he works on. He understands exactly when to use music—and more importantly, when not to.

It’s helpful to bring up Christopher Nolan’s survival thriller Dunkirk from the previous year, whose storytelling structure, like First Man’s, unveils a secret to historical filmmaking. First Man and Dunkirk both are wonderful examples of tension-building in the second act. We know how these stories end—unless, of course, the story is written by Quentin Tarantino. The third act features a skin-chilling set piece with lines that have been transcribed in the books of history. In First Man, those include “Houston, the Eagle has landed” or Armstrong’s unforgettable soliloquy on the course of mankind once he has stepped on the Moon’s surface. In this respect, it is comparable Dunkirk in that it also compensates for the tension lost.

The core of First Man’s evolution is established early on and maintained throughout—and that is through the casualties along the way, as is in Dunkirk. The purpose of these casualties isn’t necessarily to apply pressure to the main character through the threat of death—because we know that Neil Armstrong made it to the moon and back, and that the 400,000 British and French soldiers stranded at Dunkirk were miraculously rescued across the English Channel. Rather, the goal of this second-act tension-building is to score empathy points (Janet Shearon, Armstrong’s wife, played by Claire Foy, is the vessel through which Singer and Chazelle find this tension) that introduce their own form of softer tension that induces a sadness more than it does worry, a melancholy that is most effective after the climax of the movie has taken place. It is joy we feel when the fishermen show up in Dunkirk and when Ryan Gosling utters the famous “one big leap for mankind.” But Dunkirk and First Man both understand that what truly makes these stories compelling—to go even further, what truly induces us to retell these stories—isn’t patriotism, historical awareness, or personal ambition. It is individual resolve and sacrifice; all for one, and one for all.

There is a single window on screen. It’s the only one we get, and it appears to trap us. And yet, with its limited, close-up perspective, it conveys more than most open-door stories.