All over TV and in the movies, we can see that nostalgia for the 1980s is at its peak. Whether it manifests as a reboot of a popular 80s TV show like MacGyver, or a sequel to a beloved 80s film like Blade Runner 2049, audiences cannot seem to get enough of 80s-inspired media. What interests me most about this current craze are the films and shows that appropriate stylistic hallmarks of 1980s films and use them to create something new.

I find the use of 1980s film aesthetics interesting because the elements borrowed are more of an idealized version of the decade’s style. By this, I mean the things that are superficially “eighties”: in particular, neon lighting schemes and synthesizer scores. It truly embodies an aesthetic of nostalgia, the very definition of rose-tinted glasses (although perhaps, in this case, neon-pink glasses would be more fitting). Films and TV shows as varied as Drive, The Guest, and Stranger Things all feature synth-heavy soundtracks and neon lighting schemes to conjure up memories of 1980s films, even though few films from that decade actually have neon lighting schemes that aggressive.

The proliferation of 80s-inspired media is neither good nor bad; it depends on how the inspiration is used. Some films use idealized 80s aesthetics as a springboard for interesting storytelling, while others merely seek to cash in on a popular trend. To that end, I feel that two films from last year best represent the good and the bad of retro-eighties filmmaking: Mandy and The Strangers: Prey at Night.

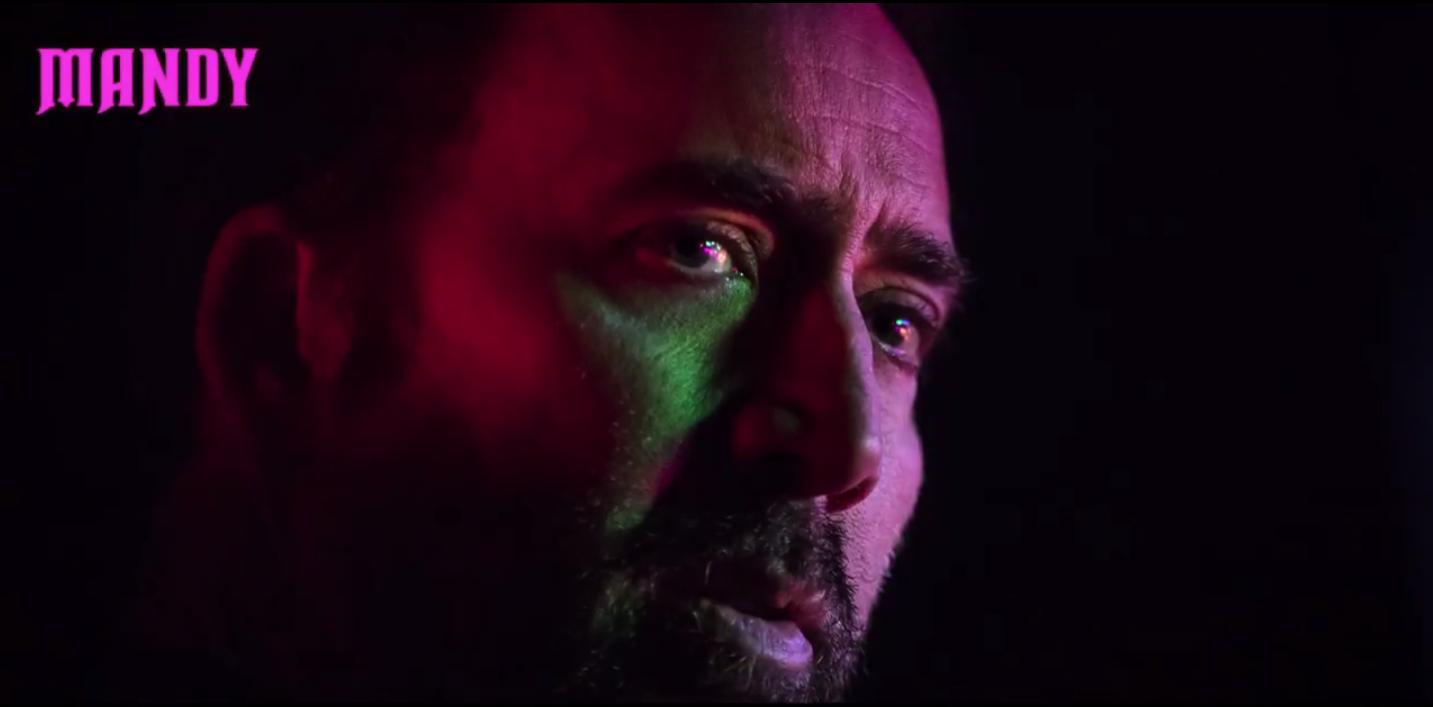

Mandy is the second film from director Panos Cosmatos, whose first film, Beyond the Black Rainbow, also draws heavily from 80s imagery. It stars Nicolas Cage as Red Miller, a lumberjack who embarks on a path of revenge after his wife Mandy is murdered by members of a cult. The film alludes to many 80s movies by including a demonic biker gang that bears a resemblance to villains of Hellraiser, as well as a chainsaw fight between Miller and a cult member that is reminiscent of the chainsaw duels in Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 and Phantasm 2.

The use of 80s aesthetics works here because it extends beyond surface-level visual presentation. Mandy leans into the fantasy genre, and the visual style helps the fantasy world that slowly emerges. Mandy herself is shown reading fantasy novels near the beginning of the film, and an early title card featuring an exaggerated, glittering silver font recalls the fonts decorating the covers of 80s fantasy paperbacks. After her murder by the cult, Mandy’s presence still seems to permeate the film, as the visuals become increasingly stylized and fantastical. The movie eventually comes to resemble the cousin of an airbrushed mural on the side of a van: Cage’s Miller roams through the neon-drenched woods, wielding a giant ax like a lumberjack-Conan the Barbarian filtered through a blacklight poster.

The score fits with the movie’s fantastical miasma. It utilizes synthesizers, as is to be expected from an 80s-inspired film, but rather than attempt to ape the sounds of that decade, it opts to distort them into a hazy memory of what the 80s actually sounded like. There are sections of ethereal, faded synths and delicate guitar that eventually give way to dark, droning ambient tones as Miller enacts his bloody warpath of revenge against the cult. The score, sounding as fantastical as it does nostalgic, sets the tone for the film.

Alternatively, there are films that only use elements of 80s nostalgia for a quick buck. Such is the case with The Strangers: Prey at Night, the belated sequel to the 2008 home invasion thriller The Strangers. This sequel treads much of the same ground as its predecessor, but with the classic sequel method of ldquo;doing it again, but bigger”. The first Strangers film featured a couple being inexplicably stalked and tormented in their remote country home by a group of masked individuals, while the sequel features a family being stalked and tormented in a trailer park by a group of masked individuals. There is nothing inherently “eighties” about this premise, unlike Mandy, which leans into the dated 1980s pop culture fear of satanic cults. And, unlike Mandy, which is actually set in the 1980s, which further warrants the use of 80s style, Prey at Night is set in the present.

This is one of the most egregious examples of pandering to 80s nostalgia—many of the retro elements in the film seem to have been decisions made in post-production in order to help an unwanted horror sequel make a profit. Most notably, the score sounds nearly identical to the score from the 1980 John Carpenter film, The Fog. On top of that, the soundtrack is a slapdash collection of 80s pop hits, placed over various scenes in the film with little regard to whether or not they are actually fitting choices. For example, there is a sequence in which a character is pursued by one of the killers into the trailer park’s community pool. As the chases ensues, the power turns on in the pool house, illuminating neon lights and blaring the Bonnie Tyler song “Total Eclipse of the Heart”. A theatrical pop ballad isn’t exactly a fitting accompaniment to a sequence where a person is being stalked by an ax-wielding maniac, but presumably, the producers felt the inclusion of that song would trigger nostalgia in the audience.

It should also be noted that the occasional use of neon lighting in Prey at Night, while certainly invoking that romanticized idea of 80s visuals, adds nothing to the plot and stands out as empty visual flourish. In Mandy, neon lighting is used primarily in the scenes featuring the evil cult and during hallucination sequences. Towards the end of the film, Miller consumes mass quantities of cocaine and tainted LSD, and thus the neon color motifs of both the cult and hallucination sequences become intertwined—a visual representation of the psychedelic state of the main character.

Invoking nostalgia can be a useful cinematic tool when used wisely. Many films borrow visual motifs or create idealized visual motifs of 80s aesthetics to accentuate their themes or moods, while others use it to ride on the coattails of a trend. It all depends on who is making the film and what they are trying to say. As we move towards a new decade, I wonder what stylistic trappings and idealized visuals will crop up as 90s nostalgia supersedes nostalgia for the 80s. I just hope more people will use it creatively, rather than for easy monetary gain.