In the age of sequels and remakes, Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival is a much needed breath of fresh air. In the past decade, science fiction films have been almost exclusively stories of alien invasions or ill-fated space travel. It is not that adherence to these tropes hasn’t yielded praise-worthy movies, but rather that courage to stray from the known “box-office success” plot lines has been in short supply. Villeneuve’s adaptation of Ted Chiang’s short story, Story of Your Life, serves as a beacon for future sci-fi movies by showing that the potential of the sci-fi genre remains mostly untapped. Like all good science fiction movies, this is not a story about the “other” descending on mankind, rather it is about humans and our inability to truly communicate with one another. It is a story of language, grief, love, and fate, and it is masterfully told.

The opening sequence is gut wrenching. The viewer watches the life and death of Dr. Louise Banks’ (Amy Adams) daughter. The mother and daughter love and fight as the girl grows to adolescence, but she is soon taken by an “unstoppable” illness. Max Richter’s Of The Nature Of Daylight accompanies the poignant sequence and pulls the viewer through Louise’s journey of love and loss. Banks introduces the first theme of this sci-fi parable in her narration: “I used to think this was the beginning of your story,” she ponders, “we are so bound by time and its order.” Louise’s reflections hold little weight at the beginning of the film, but in retrospect they contain multitudes. Villeneuve practically tells the viewer the film’s greatest secret in its opening lines, but then progresses to trick the viewer into believing something else entirely. He invites the audience on the intellectual journey that we have so been craving, and we gladly accept.

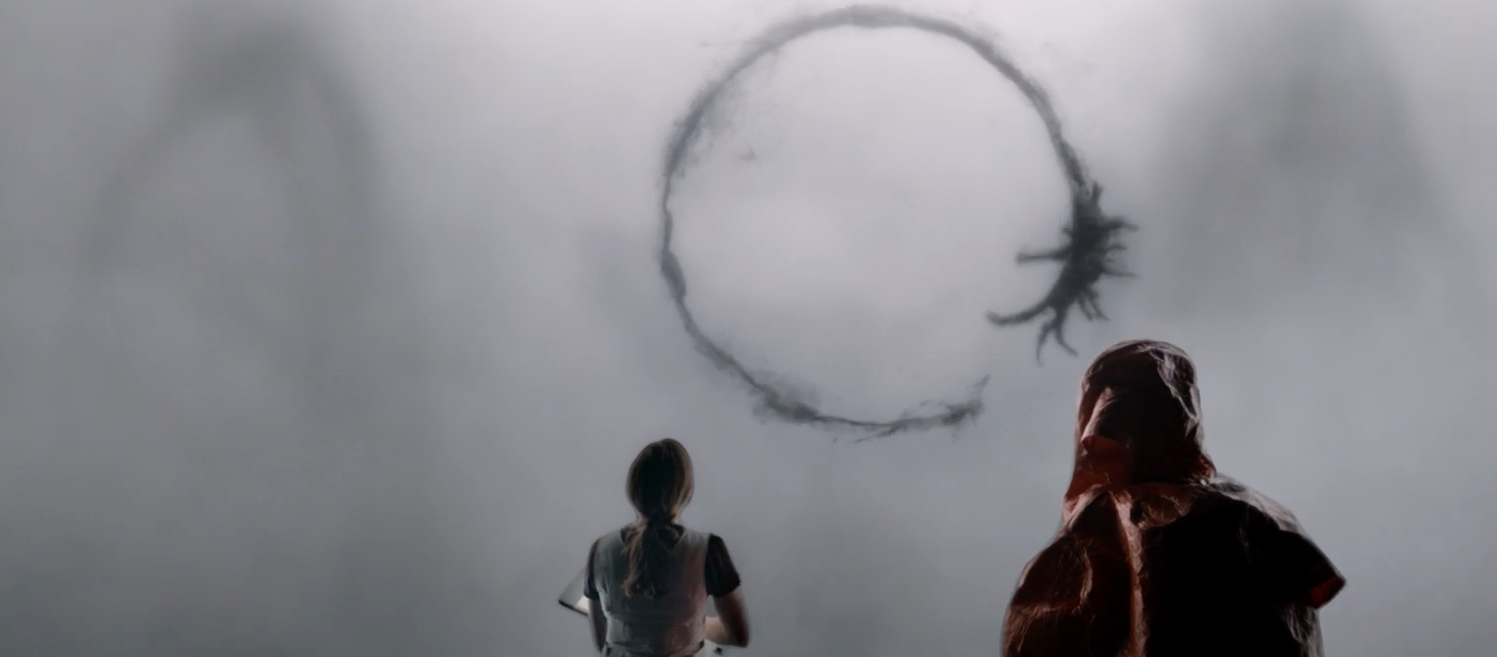

Arrival also triumphs through its sparse use of CGI. The lack of CGI and special effects allows the audience to focus on the true subject of the film: humans. There are no “Hollywood explosions” or bright blue beacons ripping holes in our atmosphere. In fact, the re-imagined depiction of the appearance of the UFO and the aliens prevents the audience from bringing any preconceived associations to the story. Arrival entirely separates itself from its predecessors with the oblong monolith and the arcane heptapods (an epithet for the aliens) shrouded by mist. Even more telling is the score of the film. Jóhann Jóhannsson’s brilliant but muted score pulses beneath the stunning cinematography. Jóhannsson’s score does not draw attention to itself, yet it is far from invisible; it is not the dramatic orchestral score that seems ubiquitous nowadays.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of this film is the symbiotic nature of its components. The score, the cinematography, the acting, the character profiles, and the screenwriting all come together like cogs to create the greater machine that is this parable. The symbiosis between every element creates a well-defined tone that resonates with the audience; it is focused and, despite having a fairly complex plot, it is not messy. In fact, Villeneuve uses a variety of methods to prevent the film from being muddled. He shifts the style of cinematography back and forth throughout the movie to indicate what is reality and what is a “memory.” The “flashbacks” that feature Louise’s daughter have vivid colors, a shallow depth of field, and a constantly shifting focal point. This is in contrast to the rest of the film’s fairly monotone and sharp aesthetic. These artistic decisions allow the viewer to more easily follow the twisting story, and, more importantly, they pull the film together coherently and deliver the message and story with intent.

Arrival is gorgeous inside and out, and it is Amy Adams performance that gives the story life. Her portrayal of Dr. Louise Banks is nothing short of genius. Banks is an unconventional hero. She is not exceptionally courageous, nor is she particularly assertive. In fact, she is surprisingly quiet and soft-spoken for a protagonist. Her heroism lies in her intelligence and her refusal to take shortcuts. Banks’ linguistic skills are juxtaposed with various nations’ inability to communicate and collaborate with one another, and so she stands as a beacon of unity in a divided world. Additionally, Jeremy Renner’s performance as the physicist, Ian Donnelly, is the perfect counterpart to Adams. He occasionally plays the role of the comic relief, but he primarily serves as a support character to Adams. Though brilliant in his own right, Renner allows Adams to stand unopposed in the spotlight.

Arrival is one of the best films of 2016, and arguably one of the better sci-fi films of all time. Equipped with impressive cinematography and a bespoke score, the film progresses past being simply “entertaining” and becomes art. Villeneuve’s manner of storytelling is so captivating that the audience allows him to take them on a winding journey. There is no desire to solve the puzzle prematurely; of course there is curiosity and attentiveness, but ultimately Villeneuve convinces us to submit to his story and allow us to learn the secret when he determines the time is right. We watch enraptured, collect clues along the way, and are still surprised when the reveal comes. And, even if you manage to predict the end or are previously familiar with it, it is nonetheless a beautiful conclusion. The final sequence of the film is once again set to Richter’s Of the Nature of Daylight. Richter’s bittersweet melody is so vastly different than Jóhannsson’s muted score—the strings overlap and rock back and forth in a repetitive pattern, while Jóhannsson’s notes are drawn out and solitary. Richter’s piece beginning and concluding the film brings the story full circle and leaves the audience wanting to see it all again.

Arrival is a uniquely intelligent movie. The tonality of the film is distinctly human, and this allows the audience to truly connect with the story and its message. Villeneuve’s deft storytelling renders Arrival an instant sci-fi masterpiece.