You all think that there is you, yourselves, and there is the world… However, everything with form changes. Everything in the world is just a result of causes and conditions.

Abbot Shibayama, quoting the Buddha in his book of essays, A Flower Does Not Talk

When COVID-19 prompted nation-wide closures and quarantining, I had just left a support system which included a group of some of my closest friends, whose proximity was largely predicated on a solid routine of watching a critically maligned movie every Sunday evening. Other friendships from that time and place remain memorialized by ticket stubs from The Shape of Water, Sorry to Bother You, and Parasite, among other wonderful films. In December the goodbyes were tearful and protracted—for months I wished and was wished well over tea and coffee and stale cafeteria food. My last night in Nashville, I took a walk past the Methodist Church and the Flat Earth Society to the independent movie theatre that had served as my place of worship and contemplation for the past several years. I can’t recall much; I probably spent my little pilgrimage afraid of the future and mournful for the past. After I moved back home I laid out a plan for 2020, a plan which was intended as much as a distraction as it was a method of accomplishing anything. The plan was extensive. Every potentially empty moment was filled, a desperate defense against any time alone with my thoughts.

Ignorance truly is bliss. Over the first month or two of quarantine, I went through all the recognizable stages of a lower-middle class white kid in peril. I read and rewatched The Lord of the Rings. I recorded and released music online. I got really into Daoism. I got addicted to social media and then got myself out of that addiction by getting myself addicted to cooking, which ended up in mixology, which I’m sure will work itself out fine.

Quarantine has been a time of discovery for some, and of loss for others, but it has been a time of loneliness for most.

The 1965 classic Kwaidan is permeated by this sense of distance—the film itself is an anthology of disparate stories taken from the Japanese text of the same name. There is little to no relationship between the characters and events of each vignette. Within the confines of their respective stories, characters frequently travel alone. They are framed in wide shots, surrounded only by landscapes made at once impossibly vast and terribly claustrophobic by the fact that they are frequently (beautiful) matte paintings. Often, the environment through which they must journey conspires against them—wind howls, snowdrifts block paths, and fog puts travelers in danger. It is in these discomforting, liminal spaces that we must take our stand against ghosts.

Kwaidan (怪談), literally means “ghost stories.” To quote Guillermo Del Toro, and more specifically to quote an English translation of El Espinazo del Diablo (2001), “What is a ghost… a moment of pain, perhaps… an emotion suspended in time.” Kwaidan’s various ghosts are forces as old as humanity itself—they are fear, they are memory, they are human nature. They are the things we wish away in the car and the shower and the night. They are loneliness. Each of Kwaidan’s four vignettes is about alienation—alienation from one’s home, or one’s history, or the people one loves. As a result of this, the horror of Kwaidan is frequently embodied in sensual, subjective phenomena. Sometimes it is the paranoia of swirling galaxies—tricks of aurora borealis, maybe, that make celestial bodies look like dozens of staring eyes. It is the way in which a spouse crosses a room. It is the way lights play in a clearing. It’s an internalized feeling of discomfort, of fear for the future and past, of anger, jealousy, complacency, and suspicion, in which the characters have allowed themselves to become trapped. There is, in each frame of Kwaidan, the sense that the ultimate danger is that of becoming a ghost, not being killed by one. In the ever-dimming world of one who is haunted (whether by a ghost, or a memory, or a feeling), the world becomes less tangible; more surreal. People are harder to reach. A ghost, Kwaidan teaches us, is a soul whose loneliness and alienation has fully consumed them.

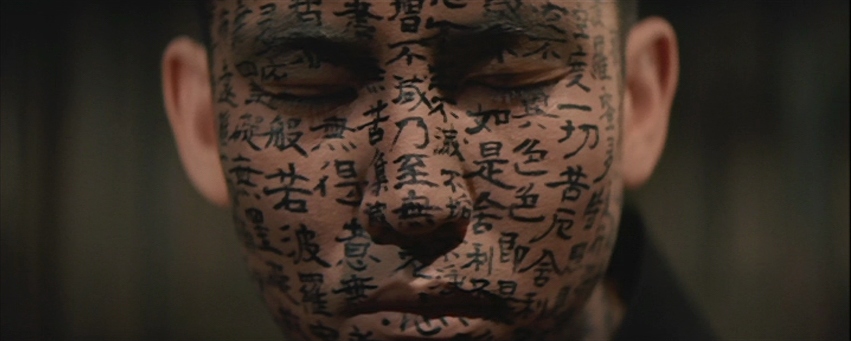

The vignette “Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi,” or “Hōichi the Earless,” features the only protagonist in Kwaidan to escape his story better off than he entered it. How does Hōichi escape? He listens to the friends he has made in his vulnerability as a blind man. His ghosts attempt to drain him of his life by forcing him to endlessly memorialize them in song. Hōichi then allows his fearful friends at the temple to delicately ink the entirety of his naked body with the text of the Buddhist Heart Sutra, rendering him invisible to the spirits. It should be pointed out that, as the men write on Hōichi’s eyelids, the film utilizes one of its few extreme close-up shots. It is an extremely intimate moment, and in a film with as much alienation, as much distance as has been previously discussed, this moment of tenderness carries a great weight. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that, in a movie featuring a monk covered in Buddhist scripture, what is present is not always as important as what is absent. Hōichi’s story plays with what is observable and what is not. Although the story ends with him losing his hearing, he knows his inability to sense his instrument and the people around him except through touch does not mean they are absent. Hōichi stays at the temple after his haunting, committing his life to his music and faith in the company of his closest friends. In “Hōichi the Earless,” safety ultimately lies in the things no one can see, a brilliant reversal of so many of the tropes associated with ghost stories. What Hōichi teaches us is that the intangible is made no less real by its lack of form. Whatever keeps us present, whether it be friendship, faith, or avocation, is just as real as the things that haunt us.

In quarantine, many of us have experienced hauntings in one sense or another, because haunting is what happens when you are forced to come to terms with yourself and your circumstances—when you are trapped in a house full of memories, full of ghosts. It has been a time of sadness for some and discovery for others and of fear for most, but it seems it is nearly over. Things will change—they can only change, and when they do they sometimes improve our circumstances, and sometimes they do not. Sometimes they keep us away from the people and things we love, but they never fully separate us. In our story, as in Kwaidan, there is no exorcism, there are no portals to close, and there is no earthly business to resolve. There is only this temporary emptiness, a facsimile of vastness