Since the early days of moviemaking, filmmakers have wrestled with the concept of adaptation. Some works lend themselves to the medium of film better than others, while other works are much more difficult to translate into conventional cinematic structure. With Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, the new film from beloved fantasy filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro and Norwegian horror director André Øvredal, the challenge is to find a way to adapt a series of short stories into a coherent narrative. Del Toro and Øvredal grapple with this challenge in an interesting, if not formulaic way.

“Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark”, the children’s book series by author Alvin Schwartz and illustrator Stephen Gammell on which this film is based, is a series of three books—each of which contains horror-themed stories and poems. Rarely do the stories, which are meant to be read aloud, run over a few pages in length. Their rhythmic pacing and emphasis on dramatic pauses make them more akin to a campfire tale than material for a feature-length film. The film version of the series raises the question: how do you adapt a disparate group of short stories into a coherent narrative?

The film’s writers had a number of ways to approach this story. The seemingly obvious choice would be to adapt a selection of stories as an anthology film and to recreate the stories in a series of vignettes. However, though horror anthology films are not uncommon, they are not known for making money. It’s possible that the filmmakers kept profitability in mind and opted for a less literal approach, instead creating a single traditional narrative that weaves in elements of select stories.

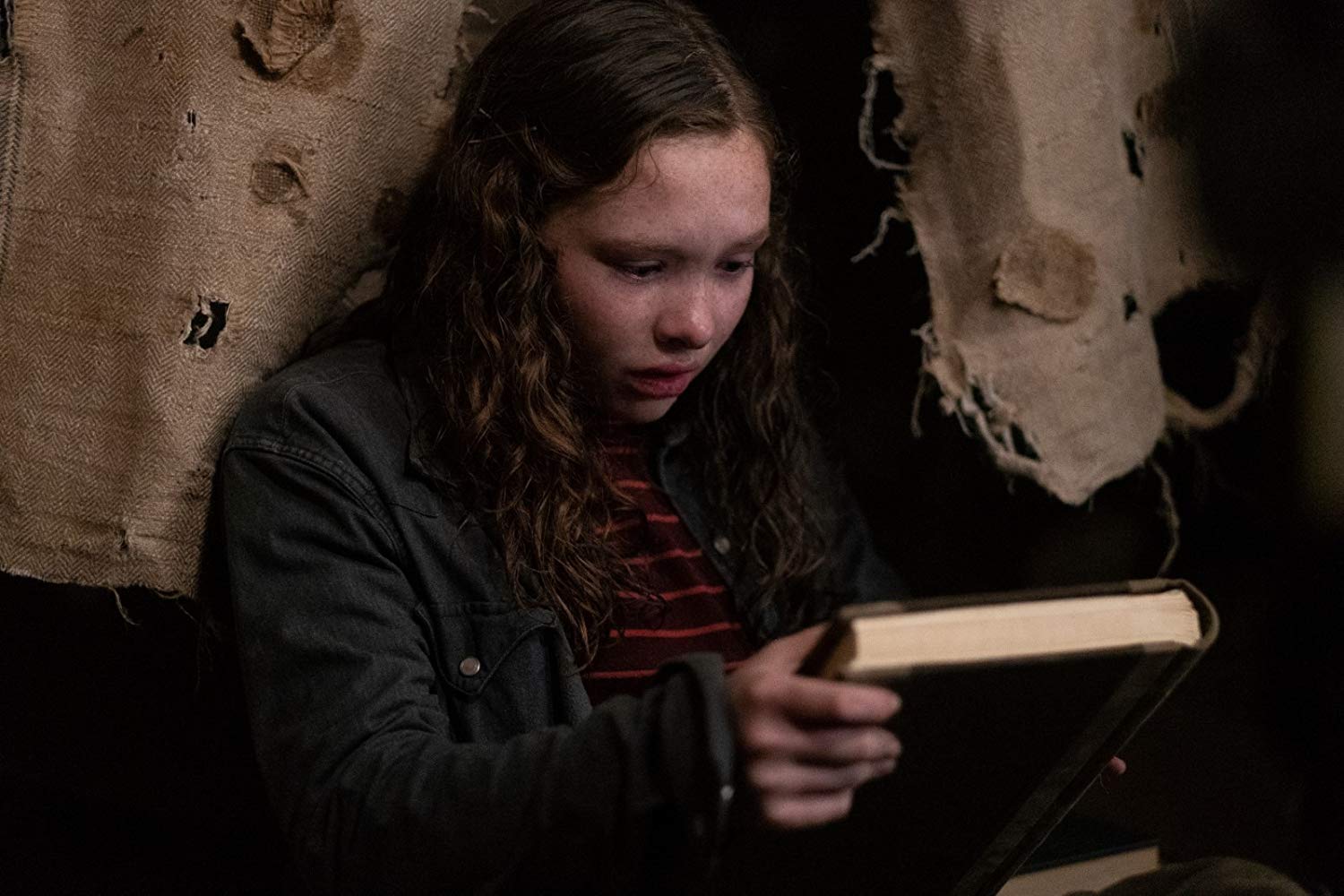

The narrative of the Scary Stories movie follows teenage horror aficionado and aspiring writer, Stella Nicholls (Zoe Margaret Colletti). Stella and her friends are terrorized by various monsters after taking a book from a haunted house once inhabited by a purported child murderer. The book in question is full of—you guessed it—scary stories. The author of the book is the mysterious Sarah Bellows, the woman who was allegedly responsible for the death of several local children in the late 19th century. After being removed from the house, the book begins writing in itself, words magically appearing in bloody red ink. The stories that appear in the book use the names of people in Sarah’s life, who then meet their doom shortly after their names are mentioned. It’s up to Sarah and her friends to uncover Bellows’ mysterious past and stop the deaths via the haunted book before everyone meets their grisly fate.

The haunted book in the film is where the material from the “Scary Stories” books comes into play; the stories in Bellows’ book that dictate the deaths of the people named in them are adapted from the source material. Luckily for the filmmakers, they have a variety of stories to draw from, and an even creepier menagerie of monsters to stalk the teenagers. The “Scary Stories” books are perhaps most famous for Gammell’s unnerving illustrations, which feature all manner of misshapen and decaying ghouls. A few of the monsters from the books’ illustrations are translated (unaltered) to the screen, although the filmmakers still saw fit to throw in a monster of their invention, the “Jangly Man”, for good measure.

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark is a peculiar adaptation because it takes a variety of stories ranging across time and location and funnels them into the setting of rural Pennsylvania in 1968. I’m not entirely sure why the specific time period of 1968 was chosen, except perhaps as a way to eliminate cell phones and other modern means of communication from the film. It seems like the filmmakers are trying to draw comparisons between the social anxieties of the late 1960s and the social anxieties of today, but the comparisons don’t connect in a meaningful way to the story of the haunted book. More often than not, this film’s version of the 1960s feels eerily similar to the 1980s of Stranger Things, what with the retro visual cues of teens using walkie-talkies and riding bikes lifted from Amblin Entertainment films of the 1980s.

The odd period setting and the rote “solve the mystery of this ghost to put their soul to rest” plot don’t quite work, but when the movie draws directly from the “Scary Stories” books, it briefly feels like a spooky good time. Many stories in the “Scary Stories” books are adapted from folklore and urban legend, so when the film draws from its source material, it feels as eerily familiar and surreal as the stories themselves. The movie is at its best when it embraces the truly bizarre parts of “Scary Stories”: spiders crawling out of zits, a severed toe floating in a pot of stew, a dog talking, and a musical motif featuring the old kids song “The Worms Crawl In”, among other oddities. The monsters are remarkable, too. The blend of computer effects and actors in costumes leans a bit too heavily on CGI to be truly effective but still musters up some of the creepiness of the original drawings.

“Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” is not exactly an easy work to adapt. Much like its fellow children’s horror series, “Goosebumps”, it faces the problem of condensing a vast number of stories into the confines of a typical feature film. Coincidentally, much like the Goosebumps films, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark uses the narrative device of a haunted book as a means for the real-life books’ material to enter the film. This allows the filmmakers to cherry-pick the most marketable elements of the source material—which is, in both cases, the monsters—and ditch the distinctly literary repetition and simplicity of the kids-book narratives in favor of conventional Hollywood storytelling.

Given the relative success of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark and its family-friendlier cousin, the Goosebumps films, it seems like a sequel might be in the works. Those who actually find themselves invested in the story and characters will probably find themselves hoping for one, since this film ends with unresolved plot threads that leave enough room for another film. If that happens, I wonder if the filmmakers will continue with this format, considering that this film seems to use up all of the iconic stories and illustrations. Perhaps a sequel with a different approach to adapting the remaining source material might prove a little more fruitful.