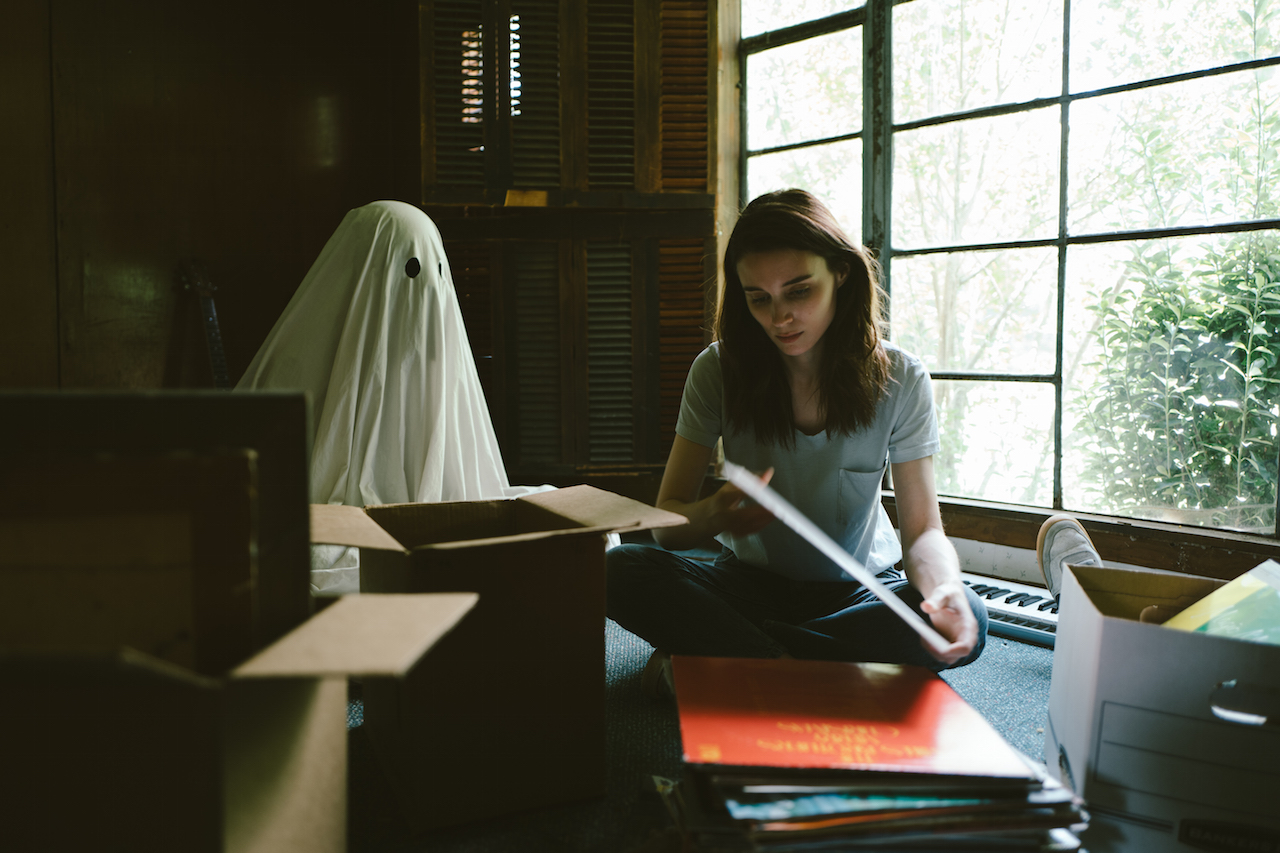

In A Ghost Story, David Lowery has crafted a stunning evocation that floats through moments of love, loss, heartbreak, and legacy. Despite navigating these complex and intricate themes, the film’s simplicity holds it together: the plot is straightforward, and we never dive too deeply into any one moment. It follows Casey Affleck as a ghost in a bed-sheet after his death, as he wanders through space and time, exploring what it means to be dead, and more prominently, what it means to be alive. In each of the events portrayed, the audience witnesses the contrast between the insignificance and significance of the moments that compose life. To create this effect, David Lowery is never afraid to break rules or risk alienating audiences.

The first thing I noticed while watching A Ghost Story was its atypical 4:3 aspect ratio, which was inspired by the 2012 drama Post Tenebras Lux. This aspect ratio takes the audience out of their typical film-viewing experience and transports them to another time and world—giving the viewer the sense that the filmmaker is not afraid to experiment.

Lowery’s use of long takes throughout the film creates an unsettling result, often trapping us in moments where the characters are most vulnerable. These moments feel private, and just like a fly on the wall or the ghost in the film, we stay stagnant, simply observing. When the camera does move, it does so with a mind of its own. Like a spirit drifting through the film, it often moves unprompted, revealing or hiding things from the audience as it wishes. A Ghost Story breaks many traditional camera rules, and to great effect. The film constantly crosses continuity lines and important actions play out of focus. Lowery’s consistent visual style fits perfectly with the poetic feel of the movie.

Another well-utilized tool is the sound design and music. In the beginning; A Ghost Story’s soundtrack is haunting and mysterious, setting us in the world of a seemingly typical film about ghosts. However, as the film continues, the soundscape opens up, using a blend of classical compositions and techno-ambiance music to create a sense of wide space and nostalgia. We also get various uplifting digital ballads that contrast the loneliness of our ghost protagonist and provide a barrage of bittersweet moments that allow us to appreciate the beauty in some otherwise dismal scenes. Lowery also uses silence to great effect throughout the film: contrasting the intense audio of musical moments with a silent aftermath lets us reflect and feel their impact.

Lowery’s editing cuts boldly through space and time, using mirrored images and transitions to drag out moments and smoothly blend decades together. The movie works in a circular pattern, touching on the same moments multiple times from different perspectives. This editing and usage of time makes the film feel detail-focused and all-encompassing at the same time. We also experience this contrast from the minimal use of locations. When the film finally does leave the claustrophobic house in which Affleck’s ghost was confined, it expands to vast fields and construction sites before returning to the room where the film began.

Though Casey Affleck has very little traditional screen time in the film, he committed to his role under the bed sheet in every shot he could. As the ghost, Affleck purposely works as an empty avatar that the audience can latch onto, rather than portraying a certain physicality as a character. With its simple movements and actions, the ghost becomes an objective character that doesn’t react strongly to many situations—withholding the release of emotions. Rooney Mara also gives a fantastically subtle performance. Similarly to the ghost, her emotions are buried deep, which allows a pressure cooker of feelings to build. The most dialogue in the film comes from Will Oldham, who breaks the largely silent atmosphere of a ghost story to give us a six-minute monologue about the insignificance of everything. The scene questions the intention of art and raises questions about the film itself before laughing it off. It is a monologue that comes directly from Lowery questioning everything—even his own reasons for making this film. As Lowery later stated, the monologue, like the film, is not about coming to a conclusion about anything, but rather, reaching for it.

There is a subtle current of humor that runs through the film, mostly stemming from the elementary-school level ghost outfit that we are immediately expected to accept as the actual dead. As Lowery stated in interviews, humor is a great gateway to emotion, and A Ghost Story‘s simplicity comes off as childish in the best way possible. The film curiously explores the world with a clear head and no judgment. The film must also be appreciated for the love it radiates. After coming off of much larger productions, Lowery wanted to make a small movie that carried no expectations so that he had the freedom to experiment. The result is a film made with friends and that comfortable collaboration shines through A Ghost Story.

A Ghost Story is a special movie that explores untethered moments and emotions with a very clear vision. Lowery’s passion project is a must-watch for anyone with a patient eye and an interest in the great questions of life. It is a beautiful vision from a filmmaker who is well-aware of all of the tools in his belt and knows just when to use them.